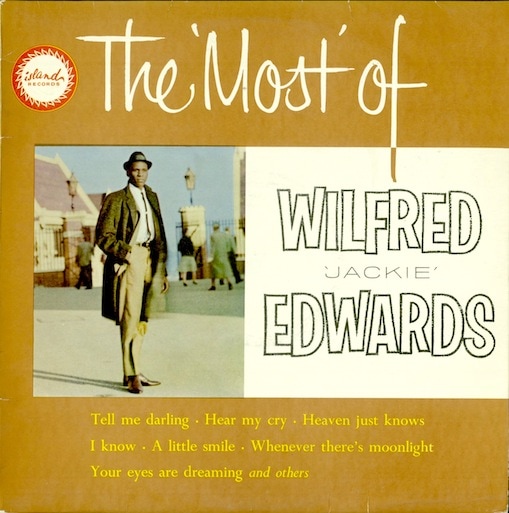

Jackie Edwards

No one, but no one in Jamaica could out-smooth Wilfred ‘Jackie’ Edwards. His honeyed tones graced innumerable soul, reggae, pop, R&B and gospel records during his lengthy career. Coupled with his flair for extracting the best from a song without apparent effort was his gift as a songwriter; he penned many of his own songs, as well as supplying hits for artists as diverse as Higgs & Wilson and Spencer Davis. He was no stranger to the record producer’s chair, being responsible for much of the output of Trojan’s Bread subsidiary from 1970 to ’72. He’s even a known name on the northern soul scene thanks to a series of stomping UK-recorded soul singles. The multi-talented Mr. Edwards was without doubt a major figure in the story of West Indian music.

Born Wilfred Edwards in 1938, like most Kingston youths he developed a love of music in his teens, and like quite a few of them he wanted to sing. The mid-fifties saw numerous talent contests taking place around the town, some in theatres, others on the radio. The most prestigious was run by Vere Johns Jr., as singer Brent Dowe later recalled: ‘Vere Johns was a man dedicated to music. He used to take the youth off the streets of the ghetto. Everyone was in the same category and could win through the crowd reaction.’

The rewards were not always great, but competition was keen, with the contestants probably valuing the respect that they gained from their performances as much as any financial benefits. Future stars of ska and reggae vied with each other, youngsters like Derrick Morgan, Owen Gray, the Downbeats (including future top London man-about-reggae, Count Prince Miller) and the lad who was still known as Wilfred Edwards. Whereas Derrick in his formative years tried to rock it like Little Richard, and the Downbeats essayed the harmonies of U.S. doowop groups, Edwards modeled his style on smooth balladeers such as Jesse Belvin, Johnny Ace and Nat ‘King’ Cole.

These youthful talents did not escape the notice of Chris Blackwell, a white Jamaican and Old Harrovian who in 1958, at the age of 21, became one of the first record label owners on the island when he set up R&B Records. His initial success came with the established Cuban-born singer/pianist Laurel Aitken, but by 1959 he was taking the cream of Kingston’s youth talent into the studio, releasing singles by Owen Gray, the Downbeats, the explosive Lord Lebby and of course, Wilfred Edwards.

Over the ensuing months, Edwards cut a series of hugely popular self-penned numbers, including ‘Your Eyes Are Dreaming’, ‘We’re Gonna Love’ and ‘Tell Me Darling’, becoming the island’s most popular narive born recording artist.

In 1962, with the coming of independence to Jamaica, Blackwell moved to London where he set up what would become the mighty Island Records. During its first months of life, it was far from mighty: operating from his London home, Chris would hurtle round the capital in his Mini-Cooper flogging his latest releases, his newly-recruited assistant Dave Betteridge would trundle round other shops doing the same thing from the back of his van, and the sales force was completed by… Wilfred ‘Jackie’ Edwards delivering 45s to the outlying suburbs on the bus.

As these discs must often have included some of his own recordings, this scenario would be akin to a present-day record shop owner ordering the latest Robbie Williams CD, then stepping back in amazement as the cheeky chappie from Stoke trots through the shop doorway carrying a 50-count box of them.

For, amongst the ever-growing West Indian communities in cities like London, Nottingham and Birmingham, the man now known sinply as Jackie Edwards was just as much a household name as Mr. Williams is in present-day Britain. He even made his major-label debut (on Decca) but, as has happened many times since, the big boys didn’t understand the market, the record didn’t get played where it needed to be heard, at the Q Club or behind the counter of Orbitone Records for instance, and it sank without trace.

Jackie also had titles out on the new Island offshoot Black Swan in 1963, including ‘Why Make Believe’ and ‘The Things You Do’. Amongst Blackwell’s other artists was hit making, firecracker-voiced ‘Blue Beat Girl’, Millie Small. The astute Island boss realised that the smooth Edwards and the squeaky Millie could vocalise together in the style of US duos like Shirley & Lee or Gene & Eunice – artists whose American heyday was long gone, but whose romantic sides still had a keen following amongst West Indians. Indeed, tunes like ‘The Vow’ and ‘This Is My Story’ by Gene & Eunice, issued on Vogue Records in the late 1950’s, were still being repressed when the label changed its name to Vocalion in the mid-sixties. This was almost entirely due to demand from first-generation immigrants, and so these songs were logical choices for Jackie & Millie to cover.

In the mid-sixties, Jackie was a busy man. As well, as penning three big hits for fellow Island artists the Spencer Davis Group, ‘Keep On Running’, ‘Somebody Help Me’ and ‘When I Come Home’ (which, like Millie’s hits, were leased to the major Fontana label to ensure nationwide pop distribution), he became something of a soul star himself, cutting another big-selling late-nighter, ‘He’ll Have To Go’ for Island‘s new EMI-distributed Aladdin label, and waxing soul dance tunes, both solo and with Jimmy Cliff, of which ‘I Feel So Bad’ became an enduring Northern spin.

In 1969 he had another crack at major-label success, signing to CBS‘s soul imprint, Direction. Unfortunately, neither his revival of ‘Manny Oh’, a song that he had written for Joe Higgs and Roy Wilson a decade earlier, nor his version of one of the hottest tunes with the new reggae beat, the Bob Andy composition ‘Too Experienced’, made much impression. with CBS unable to get their disc into the shops where it would have counted and their regular soul clientele weren’t interested.

Undaunted, he hooked up with Trojan as the new decade dawned. Here he had the scope to work as an artist and a producer, with the reggae giant releasing many of his sides on their main label and also on Bread, where he produced singles on himself, Gene Rondo and his old talent contest adversary, Count Prince Miller from the Downbeats.

In the mid-1970s the call of the Isle of Springs proved hard to resist, and he moved back to Jamaica. The astute and prolific producer Bunny Lee lost little time in tracking him down and sooin after the pair were collaborating on a variety of material, including the roots flavoured ‘What You Gonna Do’ ‘King Of The Ghetto’, ‘So Jah Say’ revivals of past glories such as ‘Tell Me Darling’ and ‘Heaven Just Knows’ as well versions of as soul, R&B and pop songs like Billy Stewart‘s ‘I Do Love You’, Gene Pitney‘s ‘If I Didn’t Have A Dime’ and even recorded Elvis’ ‘All Shook Up’.

As the 1980s progressed, he eased off from recording. Fortunately he had maintained good royalty deals with Island Records that enabled him to live comfortably. That label’s former second in command Dave Betteridge remembers Jackie coming over from Jamaica to Island’s London office a couple of times a year and collecting his cheque, doubtless combining business with the pleasure of meeting up old friends again.

Sadly, Jackie died before his time, falling victim to a heart attack in 1992 while only in his mid-fifties. With his passing Jamaica lost one of its finest singer-songwriters to date and arguably its most accomplished balladeers of all time.

MIKE ATHERTON